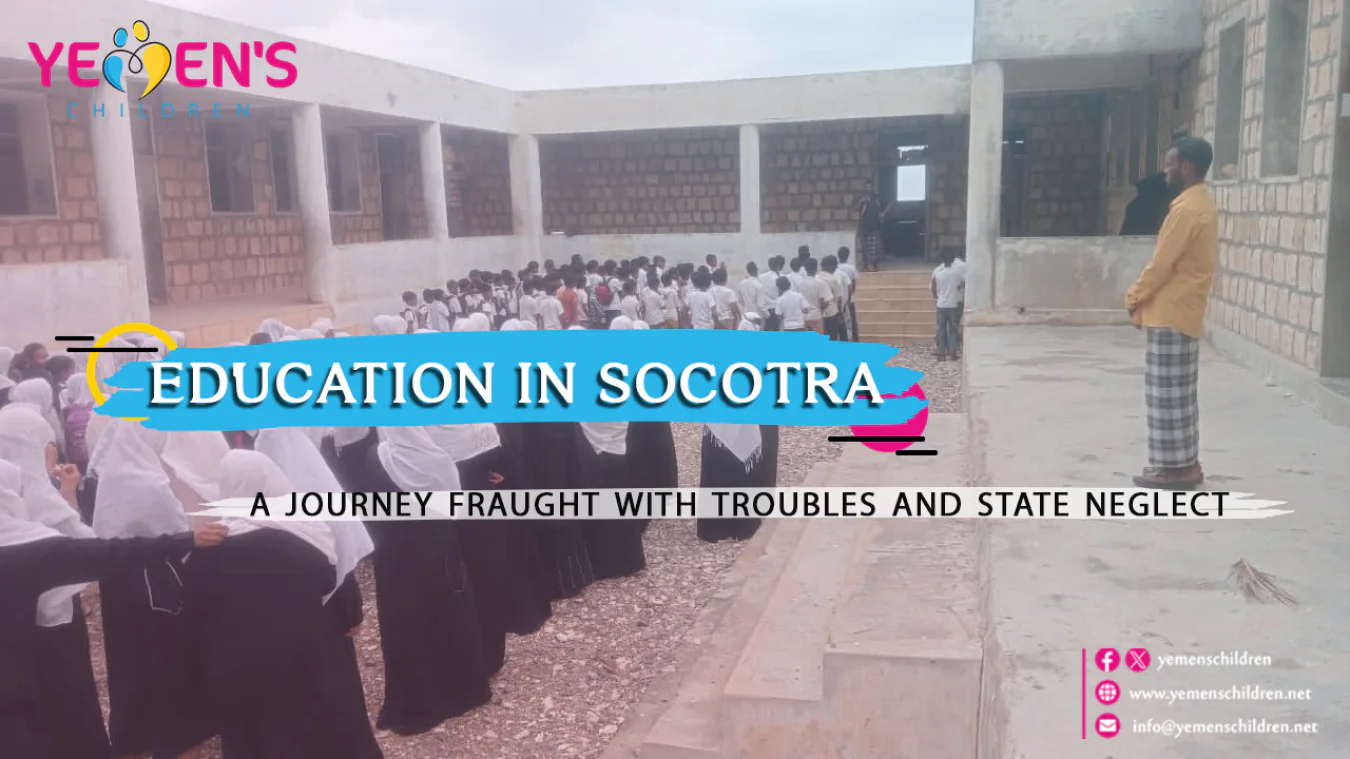

Education in Socotra.. A Journey Fraught with Troubles and State Neglect

Yemen Children's Platform - Nora Al-Dhafiri

In the middle of Socotra Island, where the picturesque nature meets the harshness of the conditions, lives Ahmed Saad Muslim, an eleven-year-old boy. Every morning, Ahmed begins an arduous journey from his small village, "Dhaydah Dasmu", to his school, "Omar bin Al-Khattab", the school that 28 villages depend on for education, which is an hour and a half walk from Ahmed's house.

Ahmed is not like his peers who reach their schools easily. He says in his small voice heavy with fatigue: "I used to sleep thinking about the long distance I would walk, as I would arrive at school exhausted. Sometimes the sun would burn me, and other times the strong winds would blow me away."

In the morning, there is no breakfast to fill his small stomach with energy, a cup of tea and some bread. This is all Ahmed finds before he begins his long journey on foot. When he arrives at school, there is no cafeteria or grocery store. He says: "At break time, we only drink water. Hunger accompanied us all day, so much so that we could not concentrate on the teachers' explanations because we were thinking about hunger and the long road back."

This year, a benefactor provided a car to transport Ahmed and a group of his classmates to school for the first time. Ahmed feels comfortable going and coming back, but he fears the future, wondering: "What if the car is not available next year? Will we go back to walking in the sun and getting tired?"

Schools without features

Ahmed says that the classrooms for the younger grades are just tents or huts, while the new building is only for the advanced grades. Omar Bin Al-Khattab School suffers from a severe shortage of equipment, as it does not have windows, doors or suitable yards, and it lacks chairs and necessary educational furniture. As for the textbooks, they are very few, as Ahmed and five of his classmates share one book.

Ahmed's school is a vivid reflection of the suffering of education in Socotra, as most schools on the island suffer from a lack of basic educational components. In an interview with the "Children of Yemen" platform, the Director of the Educational Guidance Department at the Socotra Archipelago Office, Ahmed Ibrahim Khaled, says that many schools in Socotra need to be rehabilitated, as schools suffer from a severe shortage of furniture, as there are no laboratories, educational tools, spaces in schools for activities, and chairs to cover all schools, despite the ministry's repeated demands to fill the deficit, but the response to this is completely absent.

He adds that for more than five years, there are only a few copies of school books for some subjects and some do not exist at all, as only a copy is distributed to the subject teacher, who in turn summarizes the lessons for the students.

The number of primary schools in the Socotra Archipelago has reached 64 schools, and the number of secondary schools is 6 schools distributed across the cities and countryside of the island, and the number of students in primary education is about 19 thousand, with females constituting the highest percentage of male and female students, while in the secondary stage the number of students is about 3 thousand.

Ahmed Khaled also points out that the number of private schools is four schools, and most of them do not meet the conditions in terms of the suitability of the school building, as the office has exceeded that in order to accommodate the students in the study, as the enrollment of these students in public schools constitutes great pressure for them due to the insufficient classrooms in the school building.

He stresses that the office needs to add more than thirty classrooms distributed among the schools and build more than twenty private schools in the capitals of the directorates that are witnessing great pressure, as the average number of students in the classroom has reached between (60 and 65) students, which makes it difficult for teachers to perform their role in managing the class and implementing the lesson according to the required technical standards.

Unqualified educational cadres

Ahmed Khaled explained the reality of education in Socotra, where the education sector on Socotra Island witnessed a state of accumulated neglect over decades by successive central authorities, which led to a remarkable deterioration in the educational process. Despite achieving relative progress in the eighties of the last century, which resulted in educational outcomes that contributed to some extent to improving the educational situation, this momentum did not last long. By the end of that period, education returned to a state of stagnation and decline, and it became possible to describe the educational situation in Socotra today as among the worst in the country, while other areas of Yemen witnessed remarkable development, Socotra remained outside this development, affected by the absence of support and attention.

Ahmed Khaled points out that Socotra suffers from a lack of teaching staff, as the majority of teachers are high school graduates and do not have any educational qualifications. In addition, no in-service training courses were provided to improve their level or develop their teaching methods, as the island's distance from the mainland had a major impact on teachers' inability to complete their university education or obtain appropriate training, due to the high costs that are difficult for many to bear.

He continues that despite repeated calls from educational institutions in Socotra, the central authorities have not taken serious steps to improve the situation, such as implementing training programs for teachers or equipping schools with basic requirements. In fact, Hadhramout University, which opened a branch of the College of Education in Socotra, has kept only two specializations (Arabic language and Islamic education) for more than twenty years, without responding to demands to open new specializations that meet the needs of education and the local labor market. This neglect has resulted in limited educational outcomes that are unable to meet the needs of educational institutions on the island.

In the same context, the head of the Youth Organization in the General Council of the Sons of Socotra and Al Mahrah Governorates, Saad Salem bin Kalmas, says that education on the island lacks a specialized educational cadre in the field of scientific subjects, and there is a shortage in the number of teachers, as we find teachers in one school with the same specialization who teach subjects that are not their specialty, and due to the lack of preparation for teachers, the teacher is given more classes than they can handle.

Dr. Ahmed Al-Rumaili, a faculty member at Hadhramaut University and head of the Socotra Heritage Foundation, agrees with Kalmas and Ahmed Khaled and talks about the emergence of a problem, which is the lack of employment of recent graduates in the educational field since 2011, in order to fill the gap in the shortage of teachers, although the graduates' specializations are limited to Islamic education, Arabic, and English, and the island lacks scientific specializations such as mathematics, physics, and chemistry.

Kalmas confirmed that the educational challenges in the Socotra Archipelago are great, and in order to keep the educational process going, students are forced to pay monthly fees ranging from five thousand to eight thousand Yemeni riyals, which are used to house and feed teachers and pay the salaries of workers and cooks, as most of the teachers come from outside the island.

Kalmas points out that the fees force some families not to educate their children due to their living conditions, or to educate some of their children and deprive others if they have more than one child.

Emirati and Saudi interventions in education in Socotra

Dr. Ahmed Al-Rumaili said in his interview with the Yemeni Children Platform that the UAE played a pivotal role in supporting education on the island, as the Khalifa Foundation for Humanitarian Works contracted with many local teachers to work in rural and remote areas. As for scientific specializations that do not have local cadres, the foundation brought teachers from outside Socotra, including teachers from Egypt, Hadhramaut and the northern regions, with generous salaries. The UAE also pays monthly salaries to teachers worth 200 dirhams.

Al-Rumaili points out that the Khalifa Foundation has restored some schools and furnished others with chairs, school and administrative tools, and printed school curricula. It also established a model school four years ago that started as a kindergarten and expanded to include primary classes up to the fourth grade, where the teaching staff in this school consists entirely of women from outside Socotra, most of them from Egypt.

He continues that Saudi Arabia has focused its efforts on filling the shortage in school curricula by printing school books, in addition to building about ten new schools through the Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program. These initiatives have helped strengthen the education infrastructure and reduce the burden on the educational system on the island.

Al-Rumaili confirms that despite the positives, the Emirati intervention had some negative aspects that affected education on the island. One of the most prominent of these effects is the militarization of Socotri youth, as the Khalifa Foundation targeted university students, especially those with scientific specializations such as mathematics, chemistry and physics, and recruited them in camps both inside Socotra and in the Emirates. This has led to a shortage of qualified cadres in the labor market, which has negatively affected meeting the educational needs on the island.

The militarization also included teachers themselves, as some of them left their teaching jobs in search of higher income by joining the camps. This drain on teaching staff has exacerbated the challenges facing education in Socotra, leaving many schools suffering from a shortage of qualified teachers.